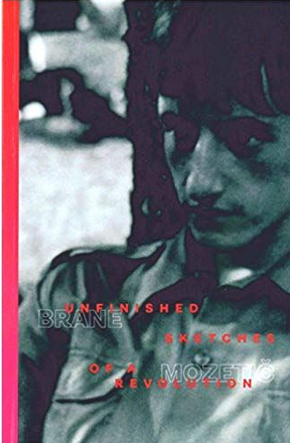

Unfinished Sketches of a Revolution

Brane Mozetič.

Northfield, MA: Talisman House Publishers, 2018.

Reviewed by Hardy Griffin

|

If you wear glasses, you’ve had the experience of looking through the optometrist’s gizmo (technically a ‘phoropter’) at the lines of letters against the wall. First the optometrist tries one combination of lenses and asks you to read the third line from the top. You say it looks fuzzy, so he flips a lens out and puts another in its place, and this time when he asks you to read it, you can make out each letter.

Now it’s the fourth line that’s unclear. Again, the doctor shifts the lenses, and so on until all or most of the eye chart letters stand in stark clarity, a crispness that is itself disorienting. One has the same sensation reading the poems of Brane Mozetič in Unfinished Sketches of a Revolution -- a juxtaposition of regional/world events with others of absolute personal intimacy. But unlike the saccharine telescoping effect we are so used to in Hollywood films, the sudden waves of clarity unsettle you, leaving you grappling with the jarring clarity of each poetic sketch. Take the following excerpts from the poem on page 15 (there are no titles throughout): |

|

in june 2001 i wasn’t allowed to enter a café because i’m a faggot. i felt like a dog. a dirty one. … how many citizens would have to be killed so that only a small nation, worthy of its name, would be left? … old bruises are opening up, spurting fire, scattering atomic rain. there are no innocent victims for us. there’s no more room for silence. |

|

The trip from being barred at a café to atomic rain falling on all us guilty sinners happens so quick that you wonder if something wasn’t skipped along the way, so you return to the poem and as your eyes move down the page, only then do you realize it all fits.

Another example, this one from the poem on page 32: |

|

may 1996, the pope’s visit to ljubljana. a historic

moment for rats and hypocrites. …we printed posters for the occasion: Roza klub welcomes the arrival of the holy father. there was a big yellow lemon on it. …when we wanted to wave to the procession with posters and banners, police didn’t let us move to tito’s street, by the railway underpass. that was their democracy. …we danced till the morning. the toilets were constantly occupied, moaning was heard, never as lustful as then. |

|

Excerpting from these poems as I have done here highlights the unsettling clarity of Mozetič’s lenses, but at the same time, I see how it doesn’t present the fullness of the poet’s descriptions. Here is the entirety of the title poem (page 16), in which you can see each poetic chunk along with the unsettling whole.

|

|

when i was little, they heated water on the fire

once a week. poured it into a bucket in the middle of the kitchen and added some cold water. then they added me. to wash me. when they were drying me off, the same water was used for my cousin. he washed himself and didn’t step into the bucket. he was quite older. and big. this is why i soon learned about student demonstrations. they told me these were dangerous. that one had to stay home. avoid revolutions. and when i was old enough, there were no revolutions. just some lame parades. this is why i started to draw sketches of resistance. they weren’t clear, they could hardly be understood by anyone. i started to revolt against the primitive world around me. it seemed that the same bucket was used for preparing the bloody mixture for blood sausages. they called for the butcher, who took care of the dirty job. probably this is where my flashes of bloodthirstiness originate. they come only once in a while, for a moment. when it seems there are still things that can be cleaned. with water. or blood. or words. |

|

Now all the lines have come into clarity, but not a clarity of completion, not a clean package. The blood, the water, the parades seep through, and you find these ‘sketches of resistance’ leave a disquieting stain.

In the poem on page 31, after a poetry reading, one listener asks, “Why do you emphasize your gayness so much in your / poetry…” Mozetič says in response that “he should read somebody else’s poems then lest he / get a stomach ulcer.” This is another aspect of this collection -- each piece crashes animalistically from one blood sausage of an idea to another. Far from irritating, this makes each transition an event, and I found myself becoming addicted to the experience. The gayness, the Slovenian-ness, the struggle between capitalism and communism, between foreignness and bare unbelonging -- perhaps the irritated listener at the poetry reading mislabeled the extreme unease running through these poems in an effort to blink or turn away from sudden and unexpected clarity. |