A NOVEL IN ROTTEN ENGLISH

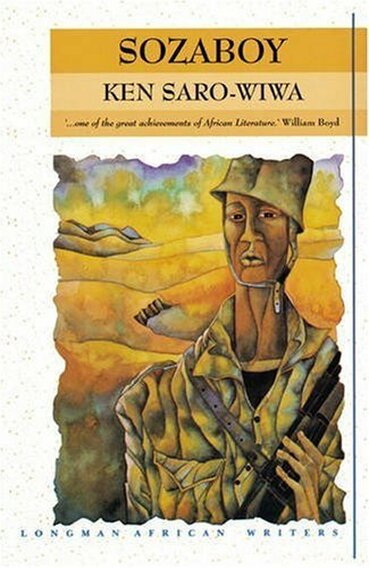

Sozaboy.

Ken Saro-Wiwa. New York: Longman African Writers, 1994.

ISBN 978-0-582-23699-8

Reviewed by Bronwyn Mills

also known as the Biafran War. Nigerian writer, Ken Saro-Wiwa,[1] chronicled that struggle, not by seizing his readers by the throat and assaulting them verbally—"ain't it awful! ain't it awful?" Rather, he simply portrayed its effect upon a humble, uneducated "sozaboy" (lit.," soldier boy") who naively goes off to fight in it. The author does it with compassion and humor, but never with scorn.

And, yes, Saro-Wiwa does it, as the subtitle of the novel itself states, in "rotten English." In his own words, the author's introduction tells us why: Sozaboy's language is what I call 'rotten English', a mixture of Nigerian pidginEnglish, broken English and occasional flashes of good, even idiomatic English. This language is disordered and disorderly. Born of a mediocre education and severely limited opportunities, it borrows words, patterns and images freely from the mother-tongue and finds expression in a very limited English vocabulary. To its speakers, it has the advantage of having no rules and no syntax. It thrives on lawlessness, and is part of the dislocated and discordant society in which Sozaboy must move and have not his being. The author modestly adds, Whether it throbs vibrantly enough and communicates effectively is my experiment. Now I have taught this novel twice, at a mediocre, overwhelmingly white university, where the majority of students sadly lacked linguistic throb. It was my experiment, teaching that book along with several other novels in a course on African literature for non-literature students; and the results of this experiment were starkly divided. Class A, on the one hand, was seemingly overburdened with the sullen and resentful: these students either put up with it at best, or, in the case of a few, read it with contempt. Class B loved it and, despite the challenge of the language, got it. Go figger, save to say that, other than basic literacy, the book's appeal does not depend upon readers' level of education or inherent eloquence. Just their imagination and sense of humanity. I sometimes think the book, among its other virtues, is a kind of literary litmus test. All that aside, and minding the fact that we hadn’t planned it this way, it is interesting that the use of a kind of endemic language, non-standard language by definition, should capture both myself and Darton, writing about Hawaiian pidgin in the preceeding review. Like Eric, I will "sidestep for the moment arguments about hegemony, colonial domination, marginalization and the construction of identity – however politically valid these may be." For one, the story reflects a world in which all of the latter imply, yes; but to revert to academic doublespeak to illuminate these is absolutely contrary to the spirit of the novel and only serves to distance the reader from its impact. I will try to stand aside and let the language Saro-Wiwa used do the job itself (and, yes, Virginia, the book does include a glossary should you need one. ) Even to this day, the lifeline for news in West Africa, is the radio (not social media); and Sozaboy—we are given no other name—opens his tale as war approaches with all its rhetoric-- Radio begin dey hala as 'e never hala before. Big big grammar. Long long words. Every time. and corruption-- We people cannot understand plenty what was happening. But the radio and other people were talking of how people were dying. And plenty people were returning to their village. From far far places. We motor people begin to make plenty money. Plenty trouble, plenty money. He goes on, I hear plenty tory by that time. About how they are killing people on the train; cutting their hand or their leg or breaking their head with matchet or chooking them with spear and arrow. Fear began to catch me small. Soon, everbody begin to fear. Why all this trouble now? Ehn? Why? Even for Dukana [his village] fear begin to catch everybody. The radio continue to blow big big grammar. As the conflict spreads, all the people of Dukana are gathered in the square to be told by the chief, Birabee, that the government needs donations of money, food ("chop") and clothing. Duzia, the cripple, then speaks: I greet the Chiefs. I greet the elders. I greet the rich. I greet the poor. I greet the brave. I greet the coward. I greet everybody. Dukia rambles, then goes on: How can a person like myself without house, without wife, without farm, without cloth to wear going to give money, chop and cloth to government? Not government dey give chop and money and cloth to porson? Now porson go being give government chop? Awright. You talk say government fit byforce porson to give them all wey dem want. Government go fit byforce porson like me to give anything? In denatured English then, why give to the government when it does not take care of its citizens? its most vulnerable? when it forces ("fit byforce") compliance in such disregard? I quote here at length to give the reader a sense of the language and the way Saro-Wiwa's "experiment" so precisely mirrors the confusion of looming conflict in an already "disordered and disorderly" world, one where as the author so wryly puts it, the humble person "must move and have not his being." (My emphasis.) Sozaboy works as an apprentice truck driver so, unlike Dukia, at this point he is doing well. Relaxing at the Upwine Bar, and after listening to several men beating their chests about being ready to fight, in that all too familiar empty and unknowing macho way, he meets a woman, Agnes. She asks him what he thinks about "the trouble," and at first he is hesitant, …for it was the trouble that made my master and myself to make plenty money…. when Agnes ask me wetin I think of the trouble, I confuse small. But he answers in such an African way, with a proverb: "'Trouble no ring dey bell,' was what I said." And then he asks the others what they think: Agnes make quick reply: "When trouble come, I like strong, brave man who can fight and defend me." One might think this discussion a bit stereotypic were it not for the language of the novel which completely engulfs the reader in the world of its speakers. Fighting as an expression of authentic masculinity, even if one does not understand what one is fighting about, much less why, becomes the rationale. It is the pro-war propagandist's way of securing support; and, as Agnes and Sozaboy become involved and marry, to no one's surprise such confused sentiments ultimate lead to his joining the army. And Sozaboy? He experiences many horrendous things: killing, not killing, camps, refugee camps, the loss of his family… It is impossible to read this book without thinking of the political sins that engendered the situation. Clearly in the Nigeria of the Biafran War—as is today, in varying degrees, even in "developed" countries—"mediocre education and severely limited opportunities" keep the war machine and the corruption machine going. To rigorously enforce their advantage with those restrictions, it appears, is the ultimate weapon of the powerful. However, there is spirit, an inherent resistance in the language which Saro-Wiwa uses to bring life to this very ordinary person, the central character of his novel. I cannot imagine his telling this story any other way. And, gratefully, the book does not end by drawing the curtain aside and the speaker holding forth in eloquent standard English: And I was thinking how I was prouding to go to soza and call myself Sozaboy. But now if anybody say anything about war, or even fight, I will just run and run and run and run and run. Believe me yours sincerely. Oh no, we who are most comfortable in "proper" usage need not be seduced into thinking we are the final arbiters of eloquence or, god help us, truthfulness. Like Diogenes, we must continue looking for the honest man, the honest woman, perhaps shining our lamp into some unexpected places, without and within. ________________ [1] Saro-Wiwa was not only a brilliant writer. He left his own honorable legacy and died in a manner which should have shamed the world: for non-violently protesting the extreme pollution and destruction of his own ethnic group's homeland, Ogoniland, by Shell Oil (Royal Dutch in this instance) and their international partners, he was subjected to trumped up charges by a kangaroo military court and hung. The area in question is in the Niger Delta and the damages of indiscriminate dumping on the part of big oil were extensive, toxic, and rendered the land unusable for even the most basic crops needed to sustain the lives of those residing there. (See the introduction to Saro-Wiwa's A Month and A Day: a Detention Diary whose ebook version can be borrowed through The Open Library; the real book, through your local library, or purchased online.) In one of those dreadful Bruegel moments, where Jesus is hung and one can barely see the tiny crucifixion in the distance for what is going on in the foreground, I happened to have walked into Ngugi wa Thiong'o's office at NYU when he was making the last phone call to groups that were trying to save Saro-Wiwa from execution. "I'll be with you in a moment," was all Ngugi could say. His and those others' efforts were in vain. |