|

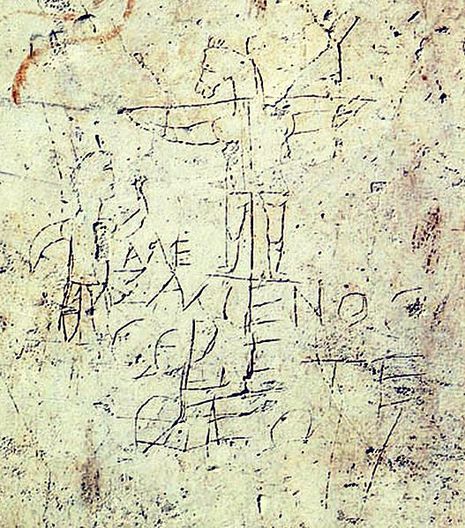

In an entry titled "Graffitti and Virgil," Steve Dodson and his linguists' blog, Language Hat, June 17, 2015, quote from Edith Gowers' TLS review of Graffiti and the Literary Landscape in Roman Pompeii, by Kristina Milnor. The subject of Graffiti, of course, is of great interest to those of us interested in a wall... Gowers remarks: "...Pompeian graffiti is not always the naive, unmediated vox populi it seems to be. These amateur scrawls often engage boldly and gleefully with the central productions of high literary culture, are as self-conscious about their materiality and creative powers as more respected literary texts, and collapse traditional distinctions and hierarchies between traditional distinctions and hierarchies between oral and written and primary and secondary to a confusing degree. Few can compete with the selfreflexivity of the following priceless specimen: “I’m amazed, wall, that you haven’t fallen down in ruins, since you bear the tedious outpourings of so many writers”. But many other graffitists draw superfluous attention to the written nature of their interventions. As well as supplementing other forms of exchange and territory- |

marking in the ancient townscape, they also stake a claim to unauthorized authorship, even to a precarious kind of immortality.

"As for the illicit character of graffiti, here it may be wrong to feed modern assumptions back into antiquity. Plutarch’s complaint incidentally makes it clear that graffiti was both normal and ubiquitous. The Pompeian site yields many surprises. For example, graffiti is found as often inside private houses as on public walls – in most of the larger houses, in fact. The same types of inscription are found in cook-shops and grand residences. Plenty are obscene, lavatorial or satirical, but few are genuinely anarchic (no “Romans go home” here). Confronted by ripe language about open legs and wet beds, scholars have tended to ascribe such compositions to underage pranksters or subversive types going about their business after dark. But Milnor argues that writing on walls in antiquity, though unlicensed, was just another dimension of normal civic activity. In a world without print, let alone radio waves, the wall acted as a blank sheet or potential billboard, one that tempted anyone with a horror vacui to fill it and engage in self-expression along with the entitled.

"But it was not always just a case of getting a message across. Pompeian graffitists seem to have been fascinated by the physical and visual aspects of writing. Latin (in)scribo, like Greek grapho, meant both “write” and “draw”, and there was a strong sense of both the interconnectedness of words and images and the talismanic allure of graphic design: in magic word-squares, for example, and laboriously produced alphabets, whether these are displaying pride in new-found literacy, symbolically representing all writing, or just testing the match between surface and implement. A whimsical doodle that advertises itself as a “game of snakes” comes in the shape of a sinuous serpent, hissing with sibilants – a spiritual ancestor to Edwin Morgan’s one-line reptilian conceit, “Siesta of a Hungarian Snake” (“s sz sz SZ sz SZ sz ZS zs ZS zs zs z”).

"Milnor reads the graffiti as carefully as any literary text, picking out clever manipulations of lines from Ovid and Virgil and the rhymes hidden in abbreviations that speak of subtle play on the aural and read experience of words. She also takes account of the original location of graffiti, which was often placed so as to initiate a dialogue with adjacent visual images. Along with crudity, she finds delicate sequences of erotic poems and even – wishful thinking, perhaps – Rome’s only personal declaration of lesbian desire. Her project fits well with other recent explorations of the fuzzy areas at the margins of canonical Latin literature: paratexts, pseudepigrapha (fakes ascribed to famous authors) and centos. In her view, one reason graffiti should intrigue us is because it shows how permeable the borders were between elite and popular culture. Street songs influenced higher genres; conversely, letter-writing etiquette and the metrical conventions of epic, drama and elegy were widely known among ordinary scribblers. The affinity between Catullus’ more aggressive poems and graffito abuse is famous (and acknowledged by him when he follows up a threat of oral rape by offering to cover tavern walls with phallic images), while the satirist Persius likens himself to a naughty boy peeing in sacred precincts and scrawling insults behind the emperor’s back."

Alas, at nearly 116 USD (from non-Amazon booksellers, nearly 100) we cannot buy the book. Not to invite intellectual property theft and to point out that the privileging of the "high" who could purchase such a volume is at the expense of the "low," we are struck by the obvious when Gowers states that graffitists "also stake a claim to unauthorized authorship, even to a precarious kind of immortality." Though Gowers and, by extension, Milnor, would dispute this in the case of the ancient graffiti on Pompeii's many walls, there is a transgressive quality about choosing to write on the Wall. From what Bowers' review states, however, the transgression is not that of the petty criminal; rather it is a transgression of class boundaries. Or perhaps a pseudo-transgression, elite culture caught slumming (that old slang term, "radical chic" comes to mind,) or low culture caught putting on the dog.

BACK TO THE WALL

"As for the illicit character of graffiti, here it may be wrong to feed modern assumptions back into antiquity. Plutarch’s complaint incidentally makes it clear that graffiti was both normal and ubiquitous. The Pompeian site yields many surprises. For example, graffiti is found as often inside private houses as on public walls – in most of the larger houses, in fact. The same types of inscription are found in cook-shops and grand residences. Plenty are obscene, lavatorial or satirical, but few are genuinely anarchic (no “Romans go home” here). Confronted by ripe language about open legs and wet beds, scholars have tended to ascribe such compositions to underage pranksters or subversive types going about their business after dark. But Milnor argues that writing on walls in antiquity, though unlicensed, was just another dimension of normal civic activity. In a world without print, let alone radio waves, the wall acted as a blank sheet or potential billboard, one that tempted anyone with a horror vacui to fill it and engage in self-expression along with the entitled.

"But it was not always just a case of getting a message across. Pompeian graffitists seem to have been fascinated by the physical and visual aspects of writing. Latin (in)scribo, like Greek grapho, meant both “write” and “draw”, and there was a strong sense of both the interconnectedness of words and images and the talismanic allure of graphic design: in magic word-squares, for example, and laboriously produced alphabets, whether these are displaying pride in new-found literacy, symbolically representing all writing, or just testing the match between surface and implement. A whimsical doodle that advertises itself as a “game of snakes” comes in the shape of a sinuous serpent, hissing with sibilants – a spiritual ancestor to Edwin Morgan’s one-line reptilian conceit, “Siesta of a Hungarian Snake” (“s sz sz SZ sz SZ sz ZS zs ZS zs zs z”).

"Milnor reads the graffiti as carefully as any literary text, picking out clever manipulations of lines from Ovid and Virgil and the rhymes hidden in abbreviations that speak of subtle play on the aural and read experience of words. She also takes account of the original location of graffiti, which was often placed so as to initiate a dialogue with adjacent visual images. Along with crudity, she finds delicate sequences of erotic poems and even – wishful thinking, perhaps – Rome’s only personal declaration of lesbian desire. Her project fits well with other recent explorations of the fuzzy areas at the margins of canonical Latin literature: paratexts, pseudepigrapha (fakes ascribed to famous authors) and centos. In her view, one reason graffiti should intrigue us is because it shows how permeable the borders were between elite and popular culture. Street songs influenced higher genres; conversely, letter-writing etiquette and the metrical conventions of epic, drama and elegy were widely known among ordinary scribblers. The affinity between Catullus’ more aggressive poems and graffito abuse is famous (and acknowledged by him when he follows up a threat of oral rape by offering to cover tavern walls with phallic images), while the satirist Persius likens himself to a naughty boy peeing in sacred precincts and scrawling insults behind the emperor’s back."

Alas, at nearly 116 USD (from non-Amazon booksellers, nearly 100) we cannot buy the book. Not to invite intellectual property theft and to point out that the privileging of the "high" who could purchase such a volume is at the expense of the "low," we are struck by the obvious when Gowers states that graffitists "also stake a claim to unauthorized authorship, even to a precarious kind of immortality." Though Gowers and, by extension, Milnor, would dispute this in the case of the ancient graffiti on Pompeii's many walls, there is a transgressive quality about choosing to write on the Wall. From what Bowers' review states, however, the transgression is not that of the petty criminal; rather it is a transgression of class boundaries. Or perhaps a pseudo-transgression, elite culture caught slumming (that old slang term, "radical chic" comes to mind,) or low culture caught putting on the dog.

BACK TO THE WALL