The Great Wall of Language:

Impromptu Notes on Migrating Signifiers & Their Uses

Eric Darton

|

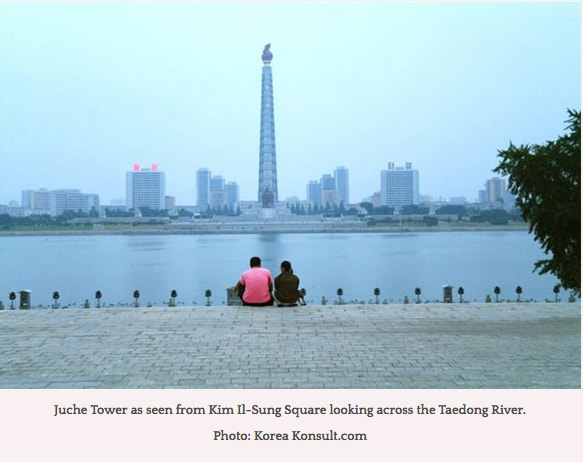

If culture and language play cat and mouse with one another across space and time, why not take pleasure in their disports? Language cannot help but articulate culture, and culture for its part runs on the tiny wheels of words and their ever shifting meanings. At this posting something unexpected is happening concerning the divided Korean peninsula. Amidst the geopolitical drama floats a charged and resonant word, albeit one unfamiliar most non-Koreans. The word is Juche, and it rhymes – sort of – with “touché.” Juche is an adaption of the Sino-Japanese shutai, coined in 1887 to translate Subjekt, from German, meaning, roughly, “the entity perceived or acting upon an object or environment.” Shutai migrated into Korean at the turn of the century and retained this meaning in translations of German-language texts, among them Marx’s writings. In 1955, Kim Il-Sung used Juche – purportedly for the first time – in a pivotal speech laying down North Korea’s line of Marxism-Leninism, and, in particular, the country’s ideology of self-reliance, autonomy and independence. Juche is often used as an antonym for Sadae, reliance on a great power. At night, one may see the symbolic flame of Juche glowing atop an eponymous tower, built in 1982 to commemorate the Great Leader’s seventieth birthday. In South Korea, Juche is used without reference to Kim’s ideology. Some scholars suggest that as a national “religion,” Juche shares principles with and may be influenced by earlier religious practices including Neo-Confucianism and shamanism. |