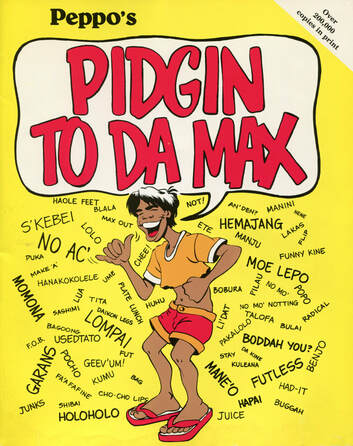

Peppo’s Pidgin To Da Max

Conceived, written and illustrated by Douglas Simonson (Peppo)in collaboration with

Ken Sakata and Pat Saskia.

Honolulu, Hawai’i: Bess Press, 1981.

Reviewed by Eric Darton

|

The book recycling shelf in the laundry room of the building where I live in Chelsea, New York, is a never-failing wellspring of remarkable reads. The most august volume I have found there is a leather-spined 1843 second edition of Alexander Morison’s Physiognomy of Mental Diseases replete with remarkable engraved depictions of such states as “Religious Monomania” and “Insane Propensity to Burn,” in both their manic and passive phases and spread over some several hundred pages.

More recently, the same shelf offered up a volume of less gravitas, though one equally fascinating: a saddle-stitched paperback, unpaginated – but containing about sixty pages: Peppo’s Pidgin To Da Max, an alphabetical dictionary of Hawaiian vernacular, composed entirely of adroitly-drawn black and white cartoons augmented with word balloons and sly, witty captions of surpassing political incorrectitude. This Remarkable Read is prompted by a confluence of my appreciation of Peppo’s art and mind, and the current activity of the Kilauea volcano on the Big Island. Some Hawaiians consider Kilauea the embodiment of Pele, honorifically Pelehonuamea, a divine female force, “the woman who devours the earth.” |

This Remarkable Read is prompted by a confluence of my appreciation of Peppo’s art and mind, and the current activity of the Kilauea volcano on the Big Island. Some Hawaiians consider Kilauea the embodiment of Pele, honorifically Pelehonuamea, a divine female force, “the woman who devours the earth.”

“Our deity is coming down to play,” said Lokelani Puha, a hula dancer and poet, and resident of the Big Island who was evacuated from the lava’s path. “There’s nothing to do when Pele makes up her mind but accept her will.”

Pele is often depicted as a mountain-shaped woman cradling fire in her hands, as though they were a caldron, or crater. One version of Pelehonuamea’s origin: she is the daughter of the Tahitian fertility goddess Haumea who had to flee in a canoe after seducing the husband of her elder sister, goddess of the sea. When she reached Hawai’i, Pele, sometimes known as Madame Pele or affectionately as Tutu Pele (grandmother), dug numerous fire pits into the earth creating an archipelago of volcanic upsurges. She is associated with the color red.

Is it opening up too wide a fissure to suggest that language also operates as a primal force brought to the surface and submerged by the tectonic plates of cultural conjoinings, rifts and conflicts? Never mind the gap – leap for it!

As the grandson of Cockneys, and therefore the inheritor of a kind of coded speech that defines even as it includes and excludes, I would sidestep for the moment arguments about hegemony, colonial domination, marginalization and the construction of identity – however politically valid these may be. For present purposes, I would prefer to listen to rumblings emanating from the molten core of human linguistic inventiveness in the face of what is best described as stress, the interaction of conflicting forces that shape human culture and topography alike. The material of Mount Everest, known natively as Qomolangma, once lay deep under the sea. The mountain may one day return there. As might the Big Island. Or Manhattan’s Freedom Tower – “Hello, Sandy II!”

While some of us are still above water, there is a distinction to be made between the way Haoles – which Peppo defines as Caucasians or people who act like them – speak and the way “native” Hawaiians do. In one frame a white, middle-aged suit-and-tied boss man leans back in his office chair and proclaims: “To get a high-paying position, one must be able to speak good English!” In the frame to the right, a do-ragged Hawaiian matron, leaning over a stove, one hand on hip, the other wielding a spatula translates: “Fo’ find a good job you gotta know how fo’ talk like one Haole!”

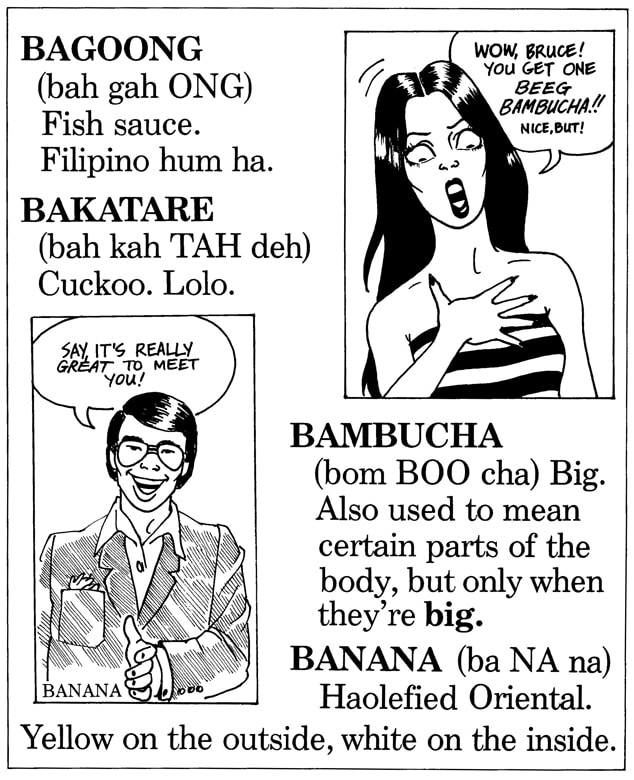

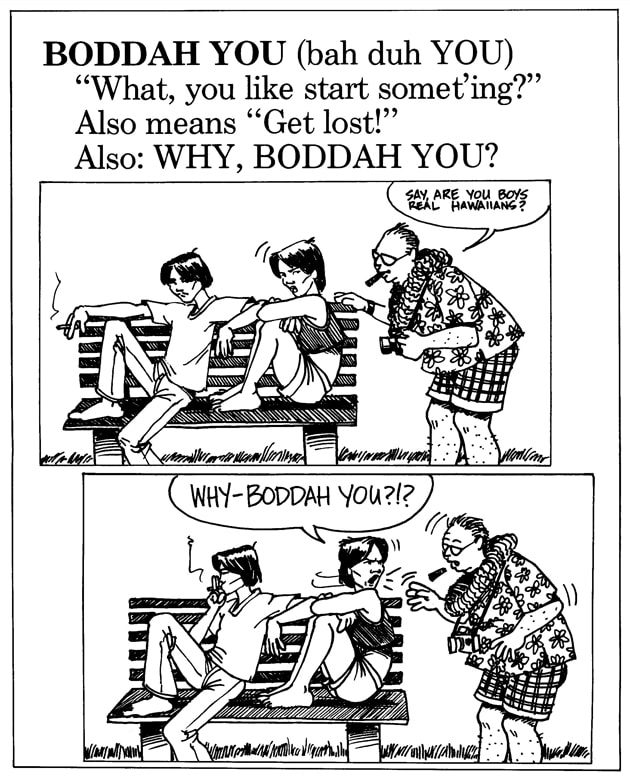

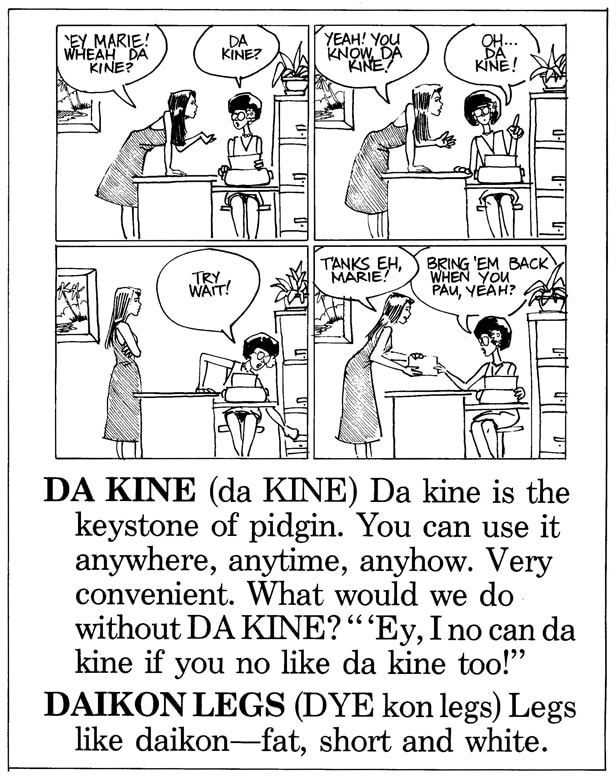

Below, a trio of representative pages I found particularly useful. Note in the second selection that “you,” when placed at the end of a sentence, adds emphasis and becomes nearly an expletive.

“Our deity is coming down to play,” said Lokelani Puha, a hula dancer and poet, and resident of the Big Island who was evacuated from the lava’s path. “There’s nothing to do when Pele makes up her mind but accept her will.”

Pele is often depicted as a mountain-shaped woman cradling fire in her hands, as though they were a caldron, or crater. One version of Pelehonuamea’s origin: she is the daughter of the Tahitian fertility goddess Haumea who had to flee in a canoe after seducing the husband of her elder sister, goddess of the sea. When she reached Hawai’i, Pele, sometimes known as Madame Pele or affectionately as Tutu Pele (grandmother), dug numerous fire pits into the earth creating an archipelago of volcanic upsurges. She is associated with the color red.

Is it opening up too wide a fissure to suggest that language also operates as a primal force brought to the surface and submerged by the tectonic plates of cultural conjoinings, rifts and conflicts? Never mind the gap – leap for it!

As the grandson of Cockneys, and therefore the inheritor of a kind of coded speech that defines even as it includes and excludes, I would sidestep for the moment arguments about hegemony, colonial domination, marginalization and the construction of identity – however politically valid these may be. For present purposes, I would prefer to listen to rumblings emanating from the molten core of human linguistic inventiveness in the face of what is best described as stress, the interaction of conflicting forces that shape human culture and topography alike. The material of Mount Everest, known natively as Qomolangma, once lay deep under the sea. The mountain may one day return there. As might the Big Island. Or Manhattan’s Freedom Tower – “Hello, Sandy II!”

While some of us are still above water, there is a distinction to be made between the way Haoles – which Peppo defines as Caucasians or people who act like them – speak and the way “native” Hawaiians do. In one frame a white, middle-aged suit-and-tied boss man leans back in his office chair and proclaims: “To get a high-paying position, one must be able to speak good English!” In the frame to the right, a do-ragged Hawaiian matron, leaning over a stove, one hand on hip, the other wielding a spatula translates: “Fo’ find a good job you gotta know how fo’ talk like one Haole!”

Below, a trio of representative pages I found particularly useful. Note in the second selection that “you,” when placed at the end of a sentence, adds emphasis and becomes nearly an expletive.

I have come to consider Pidgin To The Max among my indispensable books on language, for a number of reasons including this: however excoriating Peppo’s take may be on Haole culture as mainfest in their utterances, he likewise treats Hawaiians and their speech with the same sense of playful familiarity. Peppo seems to suggest that human beings find ways to be absurd in whatever language they speak – the height of that absurdity being to take one’s own language as an absolute standard of expressive truth. I don’t know if Peppo would agree, but my sense is that is that he is celebrating, with tongue in cheek, the dynamic fluidity of language – dangerous like lava, but fertile to da max.

In his introduction, Peppo warns that his is “not a tourist guide to pidgin. So don’t try to speak it after reading this book. You’ll just get into trouble.” But he tempers this warning with: “’Ey! Dis book GOOD FUN, brah! ‘Ass why we wen put ‘um togeddah you know: so you guys could have good fun too! But one noddah ting: we got special feeling about pidgin. ‘Cause pidgin is special. Local people, dey get togeddah fo’ party, wedding, baby luau, whatevahs, dey gotta talk story, yeah? An’ how you can talk story wid’out pidgin? Cannot! Pidgin somting from da heart!”

The last word belongs to Ms. Puha on the power and qualities of the volcanic goddess. “She is a shape-shifter who can easily appear in human form. If you see her hitchhiking, pick her up. If you have a bottle of gin, even better. Pele, like her descendants, likes a little mischief.”

In his introduction, Peppo warns that his is “not a tourist guide to pidgin. So don’t try to speak it after reading this book. You’ll just get into trouble.” But he tempers this warning with: “’Ey! Dis book GOOD FUN, brah! ‘Ass why we wen put ‘um togeddah you know: so you guys could have good fun too! But one noddah ting: we got special feeling about pidgin. ‘Cause pidgin is special. Local people, dey get togeddah fo’ party, wedding, baby luau, whatevahs, dey gotta talk story, yeah? An’ how you can talk story wid’out pidgin? Cannot! Pidgin somting from da heart!”

The last word belongs to Ms. Puha on the power and qualities of the volcanic goddess. “She is a shape-shifter who can easily appear in human form. If you see her hitchhiking, pick her up. If you have a bottle of gin, even better. Pele, like her descendants, likes a little mischief.”