Excerpt from The Purple Gang: Charlie Gruber

Allen Learst

His heart beat time with the trolley. His left hand was moist. He pressed it to the glass, as if he could block out what he knew was inevitable. Inside his pea coat, the fingers on his other hand twisted a piece of paper, folded and unfolded it: Regret to inform you of indefinite and immediate lay-off. "I'm nothing,," he thought, "nothing more than a small gear turning in the endless churn of industry." He was surprised he had kept his job this long.

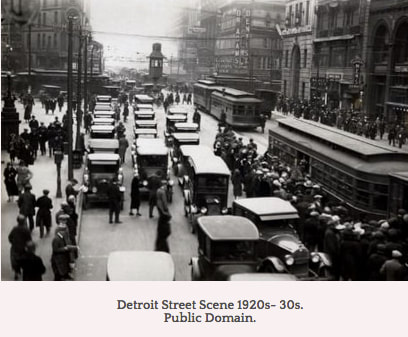

In the seat across the aisle, sat a mother and daughter, a girl of fourteen or fifteen, the hair on her legs matted under tattered nylons. She reminded him of Millie, his daughter, who danced with St. Vitus late into the night, flailing on a stained mattress. Charlie had no knowledge or concept of the Sydenham’s Chorea that made Millie dance, contorted her legs, made them kick obscenely, her face a grimace, repulsive and painful for him to watch. What hellish trick of biology was this? When Gruber looked at Millie, her pitch-black pupils were his own. How thin Millie had become, her limbs as frail as a Piping Plover he had once seen in an afternoon at the river’s edge on Belle Isle, darting and scuttling sideways. He remembered how he knelt near her bed while she curled his hair between her thumb and forefinger. It seemed to comfort her. Then she would dance, her face contorted, her feet and hands twisting uncontrollably. Time for a specialist, he knew; but how? Outside the trolley it rained, droplets of water streaked the trolley windows. Charlie saw gray saturated fedoras, the hats threadbare, ragged edges down curled as men waited, cued up for food and shelter. Rain dripped into the folds of their equally tattered blue and gray overcoats. He saw a few men he knew who had worked at the Rouge Plant. Me, too, he thought, seeing their broken spirits written all over their faces. Thousands of them from Detroit left River Rouge Plant with their eyes cast downward; they were silent, a haze of despair surrounded them. What would happen now? The Detroit United 7281 rumbled onward, the noise of mechanical turmoil and men shouting above machines subsided in Charlie’s ears. When he got off, Charlie walked two blocks south on Riopelle Street, passing his neighbors, Bill Sharp and Francis Gagnon, who played poker with him on Saturday nights before Millie became sick. Home had become dreary. An odor of sickness lingered in the hallways, seeming to drift down the stairs. His neighbors hid in their homes away from the cold and coal black smoke erupting from chimneys of four-family flats and tenements. Opening the door to his apartment, he reached deep inside himself for the hope that would allow him to care for his wife and daughter and ran up the stairs. Inside her room, Millie was asleep. When Millie did not move he was worried; when she danced, he was scared, but he saw her breathing evenly under a tangled sheet. Inside their shared bedroom, Nettie sat rocking, the rocking chair squeaking in a slow rhythm. He went to her and knelt between her legs to stop the rocking. In an even voice, with no trace of panic, Nettie said, “Delores Sharp told me the news.” “I wasn’t the only one,” he said, “I’ll find something. Don’t worry.” The empty words caught in his throat, lodged there by emotion and fear. How would he take care of them? He knew he could not cry; not now, not ever. “I’m sorry,” Nettie said, and brushed back his hair. “Something good will come of it. I just know it.” “Milly,” he said, “I don’t know…” “We’ll think of something. You’ll find another job. I’ll go to work, too. Part time. Delores said Millie could stay with her. It’s a big favor to ask, but maybe just for a few hours. We’ll be okay.” “Millie’s sound asleep,” he said. “How long?” “Just before you got here. Come, get into bed with me.” In bed, they tried to make love; but Charlie was awkward, out of step—"Sorry," he mumbled. "Don’t worry, honey. Go to sleep." But he lay wide awake, listening to Nettie's breathing, even and heavy. He turned away from her to look through the gauze curtains hanging from their bedroom window, the neighborhood growing darker; his imagination took him beyond the inhabitants of brick homes and flats stretching out along Gratiot Avenue to the northeast and to the old farms of Macomb County now in the process of being gobbled up by the expanding city, Woodward Avenue to the north and the expensive homes at Indian Village, and Jefferson Avenue to the southwest, where the River Rouge Plant belched industrial smoke into a night sky, glowing as if the Detroit River itself might be aflame with oil and gasoline. Soon the rain would turn to dirty snow. He eased himself from the bed. He stared at Nettie's pale face. The rise and fall of her breathing reassured him. The curvature of her hip had always excited him, assured him they were still young. But on this night he did not feel young, only spent. Under the sink he pried loose a board and retrieved a brown paper bag filled with money, snippets of paper, and a leather-bound ledger and went into the mudroom, where he opened a cedar chest and rummaged through gloves, woolen scarves, and mittens, knitted hats for Detroit winters. He pulled his collar tight against his neck, the leather soft against his skin. He put on a pair of cotton gloves to keep his hands clean. A cigar box sat angled precariously on a shelf above and he emptied it of screws and nails. Washers and buttons. He placed half the money inside, small bills, two hundred dollars, and pieces of paper with the bets written on them. If he wasn’t totally desperate now, he would be soon. A faint odor of tobacco and rust greeted him when he closed the lid and latched it with a bent nail. With the box under his arm, he went into the dooryard. A spade leaned against a shed. He took the shovel and crossed the grass to the edge of brown weeds against a fence and dug into the charcoal earth between the roots of a sycamore tree. In the alley he felt a fierce wind coming out of Canada. He’d never stolen from the gang he collected numbers money for. If the Purple Gang found out, he muttered to himself. Be smart. Then he turned out of the alley and found a phone booth. He made a call. "Yeah?" It was Fletcher, sounding impatient. "This is Gruber. Need to meet you." "The usual?" "Yup. Woodbridge Tavern?" "Okay. Just hurry up." A pool of neon reflected from a puddle on the sidewalk as Gruber approached the Woodbridge Tavern. A barman wearing sleeve garters and a striped shirt, swiped a wet rag over the bar and greeted him. “Whaddya need, fella?” He said he needed Abe Fletcher. The barman pointed to a booth at the rear of the building. Three fans hummed under a tin ceiling. “Bout time,” Fletcher grunted. Charlie set the bag on the table. Fletcher looked inside, . “It’s all there,” Charlie, careful to sound confident and forceful. “Looks a bit thin,” Fletcher said. “Slow week. And I just got laid off,” Charlie said. The bartender brought coffee. Charlie glanced at Fletcher's dumpling face, a nose off center, a slight overhang of brow covered with curly black hair, his head supported by a small frame, held together by hard muscle. There was a hint of sadness in Fletcher’s eyes. Fletcher laughed. “Where’s my manners? You want something to eat? Order what you want. I gotta piss.” When Fletcher stood, Charlie saw the butt of a revolver holstered inside Fletcher’s topcoat. Fletcher’s other hand was wrapped in gauze. “A bowl of soup. And bread,” Charlie said when the bartender came. When Fletcher returned from the john, Charlie studied his fists, the knuckles swollen and bruised. “What happened to your hand?" Charlie asked, and looked up from a spoon he brought to his mouth. Charlie had been in a few scrapes himself. One time he fought a man outside the factory, a man larger than himself, knocked him cold on the pavement, which came up to meet the man’s face, and caused him to bleed profusely from the corner of his mouth. Charlie feared he had killed him. How easy it was to knock him down. The man slowly got to his feet and staggered toward his car. At the circle’s edge of onlookers, a dandy in a three-piece suit approached Charlie and asked him if he had ever considered fighting, you know, bare knuckles, for money. The payoff was good—more money than Charlie could make in a week. "No thanks, I got a job," Charlie had answered. Where might that man be now? Fletcher raised one eyebrow and said he had lost too many rounds. “Went 10 rounds with that bum. “Gave ‘em a helluva show. Bum kept jabbing my kidney, which kinda puts me in a bad mood. He didn’t need to do that.” Fletcher’s eyes had lost their sadness. “There is nothing in this world,” Fletcher said, “that can imitate the sound of a man going down. Sure, the dough is satisfying and the dames and some of the men, too, fuss over 'Fletcher the punching bag.' But you ain't hanging round to hear boxing stories. What do you want?” “It’s what I need. A meeting with Albert Bernstein.” “The Professor,” Fletcher said. “He reads books and talks a lot, but don’t let the thick glasses fool you. You really want to hook up with those boys? It won’t be easy getting off that merry-go-round. Ain’t no kiddie ride. You understand?” Charlie nodded. “The Professor might need a driver,” Fletcher said. “Tell you what. You go around Frank Deluca’s, the wop’s restaurant on Gratiot, south of the Easter Market. You know it?” Charlie said he did. “You go there at eleven tonight. I’ll call Lenny Bernstein, let him know you’re coming. You handle that?” “I’ll handle it. I need to call my wife,” Charlie lied. He worried a phone call might wake Millie. Fletcher lit a cigarette, and blew smoke at the ceiling. “I understand,” he said. Charlie had a couple of hours to kill, so he wandered aimlessly up the block from the Woodbridge Tavern until he found himself standing in front of the Ambassador Theatre at 17730 John R. Street. On the marquee: Frankenstein. The public, he gathered, stood in line to escape the reality of poverty, to convince itself of its own humanity by watching a monster come to life. He had taken a shortcut through an alley behind the theater and noticed the red brick façade, the mortar crumbling, and a rat squirming through a hole. He imagined them gnawing their way into the theater; he fantasized how they might twitch along the carpet, sniffing their way into abandoned drawers filled with mildewed costumes, where they made nests and humped each other. Their cache of food might be popcorn, Candy Buttons, Rainbow Sprinkles, and the Red Hots he had devoured as a kid. On Woodward Avenue there were brightly lit storefronts, bars decorated in neon, wet streets where people walked in front of J.L. Hudson’s Department Store, S.S. Kresge's Five and Dime, the Hungarian Village Restaurant, and Sanders Bakery. The automobiles and streetcars were a mechanical distortion in Charlie’s ears. Not knowing exactly where he was or why he had come to this place, he kept his fedora low on his eyes and tried to get his bearings. He seemed to have lost his focus. He was outside of himself and thought about his family. He heard the Detroit River and its ceaseless flow toward Niagara Falls, where he and Nettie had paid five dollars on their honeymoon to ride the Grand Trunk Railroad from Detroit to Buffalo. On an observation platform, Charlie had held Nettie’s hand, knowing she was pregnant with Millie. The force and power of the water overwhelmed them. The roar and spray made them giddy with their love for one another, as if all things were possible. A freighter steamed up river. He saw its lights in the darkness, and heard the engines chug and beat against the current. The slap of water on the docks brought him back to reality. Less than a mile across the river, Windsor was a mirror of Detroit. Between the two cities, surfacing and sinking, logs bobbed in the wake of ships. Blood pounded in Charlie’s ears. The Penobscot Building lit up the night sky. He walked through a mist looking into the windows of Hughes and Hatcher, men's suits advertised as “Exclusive, Not Expensive,” and other department stores he had never entered, knowing a gift, a chemise or fur scarf for Nettie was more than he could ever afford. Men in Alpaca top coats and women in furs and capes lingered at sales counters, laughing and talking to clerks. They came out of Jacoby’s German Biergarten and the Roma Inn, places too expensive for Charlie. A Yellow Cab pulled against the curb. Charlie got in. Albert and Lenny Bernstein sat across from one another in Deluca’s Italian Diner, a conical of light on their table. Lenny motioned for Charlie to join them. Albert Bernstein's complexion was pale and pockmarked. Charlie noted how he carried himself, how his face tilted upward as if to gain a few inches in stature. When he shook The Professor’s hand, light glowed in his glasses and masked his eyes. “I’ve got to pat you down, Bub,” Lenny said. Their suits and ties, their fedoras, set on a nearby table, were obviously expensive. Albert Bernstein took a cigarette from a gold case and offered one to Charlie, which he took. “I see you are taken with my appearance, Mr. Gruber,” Albert said. Charlie fought back the rising tide of his fear. “Call me Charlie,” he said. “Please.” “I’m somewhat of an oddity,” Albert said. “Right, Lenny?” Lenny nodded and pared his fingernails with a knife. “No matter. When you have a lot of money one’s physical presence doesn’t matter. You still get what you want. Cars, Women, fine clothes. Now is all that matters. Do you believe in the future, Charlie? I mean, do you have prospects, dreams, and aspirations?” “I have immediate problems,” Charlie said, his voice twisted from his throat; all of his difficulties came forward, reminding him how sick Millie was, the money belonging to the Purple Gang he had buried in the yard. He understood the risk, but his family would come before anything. His father’s sense of humor had carried them through rough times. His mother had held them when they were sick, rocked them when they were afraid. All dead now, he thought, even the sister who ran in front of a truck loaded with illegal booze, just seven years old, and without any expenses for her funeral paid by the bootleggers. “Ah, good,” Albert said, “Problems present solutions. A man who thinks too much in the future is destined for disappointment. Take me, for example, I got a problem with this chisler they’re calling the Gray Ghost. He keeps hitting my trucks on both sides of the river, stealing my booze. Mostly in winter. Good Canadian whiskey, too. "Are you capable of taking care of business, Charlie? Take this man, Henry Ford. You worked for him, right? And it was a good job, no? So many people out of work, standing in soup lines, waiting for broth and breadcrumbs. Shameful. “Your man Ford, you see, is someone whom others call a visionary. He believes in opportunity, in the market, the American dream. It’s a story created by individuals who want control, who believe God favors them. And this makes them superior to others. But Ford dismisses thousands by the day forcing them to eat burgers and drink rotgut to protect his profit margin. You see, he’s no longer the humble farm boy turned garage mechanic; he’s a captain of industry, the one who gives orders, the one who is not to be disobeyed or questioned.” “I was a heat treat man,” Charlie said. The years he had worked at the foundry came flooding back. He remembered smokestacks and giant ladles, molten iron spilling from their edges, suspended from giant hooks inside open-hearth buildings, steel shaped and treated for the stamping plant, where twists and turns of tubular metal went inside squares and rectangles, where it coiled and took shape in configurations Charlie only partially understood. “I can see you are an intelligent man,” Albert said. This Mr. Ford, did he teach you the physical properties of metal?” Charlie shook his head. “No,” he said. “I learned it on my own. The automobile bodies, they are meant to last, unless they are exposed to a lot of salt over time, but we don’t live near an ocean, so it shouldn’t be a problem.” Albert exchanged looks with his brother and coughed at the ceiling. “Mr. Ford doesn’t care about you. You are aware of this I take it. He’s not one of us. Ego's is too large. You know what happens to people with large egos, Charlie? They die alone in the dark. This is a certainty. “Ford may have the market on automobiles, but I own liquor, and everything comes through me—all the spokes on a wheel lead to me, in much the same way Detroit’s streets are designed; it all comes from outside and ends up in the middle, except Detroit’s got no middle, it’s only half a wheel and it starts at the river’s shore, where my boats dock.” Charlie nodded. “I need work, Mr. Bernstein. My daughter’s very sick. That’s all I came to say." "Your honesty, Charlie, is refreshing,” Albert said. “In a warehouse on top of a salt mine not far from here is a 1931 Cadillac, a fine car. At 2:00 A.M., Lenny’s going to need a driver; he’ll be with another man by the name of Eddie Axler, good man, you can trust him. All three of you will pay a visit to the Collingwood Manor. It’s infested with rodents, so be careful. Give Lenny your home address and he’ll pick you up." “If it’s a driver you’re looking for, I’m your man,” Charlie said. “I’ll drive Lenny and Mr. Axler to hell and back if that’s what it takes." "I assume, Mr. Gruber, that you can exercise discretion?" " I know how to keep my mouth shut.” Albert Bernstein stood and Lenny helped him on with his tailored overcoat. When they donned their hats, he said, “When the errand is complete, Lenny will pay you five hundred dollars. The next time we need you, if you do a good job, it will double.” "Thank you," Charlie replied stunned by the amount of money. That was more than he made at River Rouge in three weeks. He suspected what Lenny and Eddie Axler were going to do, finally understood the allusion to rats, and his stomach sank. All you have to do is drive, he thought. Just drive. “Thank you, Mr. Bernstein.” Lenny held an umbrella over Albert’s head as he entered the car; they did not offer him a ride. When Charlie got home, he checked on Nettie and Millie. They were sleeping. Millie’s spasms weakened her and when she suffered them for most of the day, she tended toward long bouts of deep, deep sleep. After checking on her several times during the night he realized there was a pattern. Her body shut down, as if it were attempting to recover. He turned on a porch light and sat in an armchair and waited. He was very tired. He hadn’t slept since the night before, worried about his job; he tried to keep an eye on the street from the flat, but he fell asleep. His father was in a dream about a menagerie, the carved and painted circus wagons full of exotic animals, elephants and lions, tigers that paced and growled; they walked a perimeter inside the Big Top. Then he was on a high wire stretched taut between two poles, alone on a bicycle, a long balancing pole where, on each end, Nettie and Millie balanced him. He traversed the wire, while a crowd below jeered, the dirty faces of children, men, and women stared up at him, their eyes wide with fascination as they waited for him to fall. Awakened by the rumble of the Cadillac’s motor, Charlie scrawled a note: Please rest! Back soon, and he took a ten-dollar bill from his wallet and left it on the kitchen table for Nettie to find. He wanted to leave more, but he had to be careful. He wasn’t ready to tell her about the Bernstein brothers. He ran outside and slid into the driver’s seat. Lenny handed him a Mauser C96, German made 9-millimeter. “You might need this,” Lenny said. “Best self-loading pistol in the world. Leave it to the Krauts.” “Seventeen forty Collingwood. You know it?” Lenny asked. “Yes.” Charlie turned onto Trumbull Avenue, made a left on West Grand Boulevard, and then north on Linwood. The men were quiet. Lenny Bernstein in the front seat. Eddie Axler in the rear. Charlie watched houses go by, a stray dog crossed the street, two negro boys eyed him suspiciously. “You can’t miss with that pistol,” Axler said. “I doubt I’ll need it.” Charlie kept his eyes on the road, not wanting to show fearfulness. At the plant, wasn't a shift boss who could be trusted, he'd learned. It probably holds true for gangsters, he thought. So they smiled a lot, and showed you their teeth? Didn't mean they were your friends. “You never know,” Axler said. “Abe recommended you. He’s a good boxer, you know. We do everything together, if you know what I mean. Abe is tough, but he’s got a sensitive side. Right, Lenny?” Axler wore a tailored blue suit, a ring on the pinky and ring finger on both hands. He was dapper. His hair was slicked back tight against his head. His wire-rimmed glasses wrapped behind his ears. The bulge of his pistol strained his suit. “Shut up, Eddie. You talk too much,” Lenny said. At the Eastern Market a week ago, Charlie heard a grocer talking to a policeman. “The Purple Gang,” the grocer said, “they’re foul meat, discolored, bruised. They smell bad.” The grocer, Charlie remembered, looked around nervously to see if anyone except the copper had heard him. Despite his fear, he felt good behind the wheel of the Caddie. The car was designed well, a gleaming dash, its heater warm and inviting, V8 growling under the hood. The gear shift move easily under his palm. Nothing more than molten ore cast into a die, molecules shaped and reshaped with heat, temperature, and carbon, something Charlie understood. Charlie pulled into the alley behind the Collingwood Manner. “Leave it running,” Lenny said. Lenny and Axler got out of the car and walked toward a door marked “Deliveries.” Lenny left the door ajar. A shaft of light created a thin rectangle on the concrete. A black panel truck marked with white lettering, Cleaners and Dyers, Charlie noticed, had been parked in the shadow of the building next door and across the alley. Collingwood Manor was made of red brick, dark and shiny in the rain. Apartment windows burned yellow with incandescent light. Elm trees planted by the city had died, their broken branches littered the alley. Axler said, “This won’t take long” before following Lenny into the Collingwood. Several minutes later two muffled shots rang out, then a third, a fourth. The din seemed far-off. Charlie looked up, saw a muzzle flash in a window on the fourth floor, heard a fifth and sixth report. Someone ran from the building, someone holding his side. Charlie couldn't tell who it was. Lenny and Axler appeared at the car's side window. The panel truck behind him roared past. “He’s getting away!” Lenny said. “Follow him—see where he goes!.” Lenny threw a roll of bills on the seat. “Meet us. Woodbridge Tavern. Tomorrow. Ten o'clock. Go!” |